His journey from a small town in Mexico to rousing success in Major League Baseball inspired generations of fans and created a seismic shift in the demographics of the Dodgers fan base.

His unorthodox pitching motion, distinct physique and seemingly mysterious aura left an indelible mark on people from all walks of life, whether it was Los Angeles’ Latino community grappling with the displacement created when the Dodgers built their stadium, Mexican immigrants and their families or artists inspired by his wizardry on the mound.

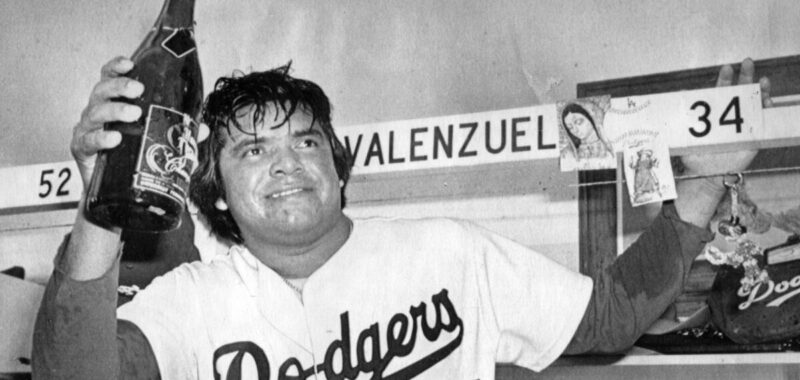

Dodgers legend Fernando Valenzuela died Tuesday at age 63. He is survived by his wife, Linda, four children, seven grandchildren and extended family.

Valenzuela’s impact endured for so long and so powerfully that the Dodgers retired his jersey number in 2023 despite a long-standing rule that the team only did so for those who were in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

It was a fitting bookend to a public baseball life that had an unprecedented beginning, a surprising and stirring stretch in 1981 that became forever known as “Fernandomania.”

And though the left-hander never quite reached those heights in his playing career again, Valenzuela remained a beloved and enigmatic hero who was never far from fans’ hearts, as evidenced by the preponderance of No. 34 Dodgers jerseys in the stands and ovations he would receive at home games when he was shown on the scoreboard while working games at Dodger Stadium as part of the team’s Spanish-language broadcast team.

“On behalf of the Dodger organization, we profoundly mourn the passing of Fernando,” Dodgers team president and chief executive Stan Kasten said in a statement. “He is one of the most influential Dodgers ever and belongs on the Mount Rushmore of franchise heroes. He galvanized the fan base with the Fernandomania season of 1981 and has remained close to our hearts ever since, not only as a player but also as a broadcaster. He has left us all too soon. Our deepest condolences go out to his wife Linda and his family.”

Valenzuela’s relationship with the Dodgers included some difficult stretches, with the star contesting his release from the team and taking years to eventually accept an ambassador role with the franchise.

How did the man who remained guarded in the spotlight all his life forge such a close and enduring connection with Dodger fans?

“Fernando is the uncle who made good,” playwright Luis Alfaro said during The Times’ award-winning “Fernandomania at 40” series in 2021. “He is the relative who is forever a superstar. He’s immortalized, he’s the María Félix of sports.”

For Valenzuela, it was a bond that was cemented early in his rookie season.

During that heady 1981 season, Valenzuela used an assortment of pitches that included a screwball to become the first, and to this day only, player to win the National League Cy Young and Rookie of the Year awards during the same season. With a windup in which he would look skyward almost as if he sought guidance from a higher power, he won his first eight starts — five by shutout — shocking longtime baseball observers.

“It is the most puzzling, wonderful, rewarding thing I think we’ve seen in baseball in many, many years,” Vin Scully exclaimed on the air after the fifth of those shutouts, a 1-0 win over the Mets in New York, adding: “And somehow this youngster from Mexico, with the pixie smile on his face, acts like he’s pitching batting practice.”

After a midseason players’ strike interrupted the regular season, the Dodgers would go on to win the World Series, beating the New York Yankees in six games. During the team’s postseason run, Valenzuela was the winning pitcher in Game 5 of the National League Championship Series, holding the Montreal Expos to one run in 8 ⅔ innings and helping the Dodgers secure the pennant.

He started Game 3 of the World Series, following two losses by the Dodgers in New York, and gutted out a complete-game, 5-4 victory despite throwing 147 pitches, giving up nine hits and walking seven. It was the first of four consecutive victories by the Dodgers to clinch their fifth championship in franchise history.

The Dodgers, longing for a Mexican star to connect with the Latino population in L.A., had finally found one in Valenzuela, whose impact would transform what had been predominantly a white fan base.

It’s a profound legacy that has lasted for generations and could be felt in tributes to Valenzuela came in as the news of his death spread Tuesday night.

“A shining light that illuminated baseball has gone out when Fernando Valenzuela passed away,” Jaime Jarrín, the Dodgers’ longtime Spanish-language announcer who retired in 2022, said in a statement. “I have lost a dear friend; a man of integrity; an exemplary father and husband who, without knowing it elevated me to an international pedestal.”

“Fernando was an outstanding ambassador for baseball,” Major League Baseball commissioner Rob Manfred said in a statement. “He consistently supported the growth of the game through the World Baseball Classic and at MLB events across his home country. … Fernando will always remain a beloved figure in Dodger history and a special source of pride for the millions of Latino fans he inspired. We will honor Fernando’s memory during the 2024 World Series at Dodger Stadium.”

“To millions, Fernando Valenzuela was more than a baseball player. He was an icon that transcended the limits of hope and dreams,” Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass said in a statement. “He was the voice of a game that we hold close in our hearts. His charisma was palpable, and his excellence was undeniable.”

For Valenzuela, 1981 was a remarkable season, perhaps surpassed only by the events leading up to it.

The youngest of 12 children, Fernando Valenzuela was born in Etchohuaquila, a small farming village in the state of Sonora, Mexico, on Nov. 1, 1960. His parents, Avelino and Emergilda, and his six brothers and five sisters lived in a whitewashed adobe house with five rooms and no running water in a community that during Valenzuela’s youth consisted of a few dirt roads and had a population of 140.

In addition to helping tend to the family’s crops, Valenzuela and his brothers played baseball. Valenzuela stood out even at a young age and by 1977, he was signed by Etchohuaquila’s local team, the Navojoa Mayos.

“By that point, I told myself, ‘now it’s a career, it’s not for fun,’” Valenzuela told The Times in 2021.

Facing players much older than him, Valenzuela successfully pitched for several teams before moving on to the Yucatan Leones of the Mexican League in 1979 by the age of 18.

By this point, he was on the radar of Dodgers scout Mike Brito. Himself a distinct figure, with his Panama hat, mustached grin and ubiquitous cigar, Brito first spotted Valenzuela when he was pitching for Guanajuato in 1978. The Dodgers scout was on hand to see a shortstop on the other team, but Valenzuela quickly got his attention.

Brito continued to follow Valenzuela’s career and lobby the Dodgers to sign the left-hander. By July 1979, the Dodgers purchased Valenzuela’s contract from the Leones for $120,000 — considered a substantial amount at the time for a Mexican player. But it ultimately proved to be a groundbreaking transaction. Major league teams had largely ignored scouting in Mexico before then. Prior to Valenzuela’s Dodgers debut in 1980, fewer than 40 players born in Mexico had appeared in the majors, according to Baseball America. That number has since grown to nearly 150.

After spending the rest of the 1979 season with the Class High-A Lodi Dodgers, starting three games and posting a 1.12 earned-run average, the organization determined that Valenzuela needed to add another pitch to his arsenal to continue to move up. Brito suggested he learn a split-fingered fastball, but no one in the Dodgers system threw one.

Then Brito remembered Bobby Castillo, a former Lincoln High and L.A. Valley College star who had spent parts of three seasons with the Dodgers, threw a screwball. Despite language barriers — Castillo did not speak Spanish and Valenuela did not speak English — Castillo taught Valenzuela the screwball in the Arizona Instructional League.

Valenzuela caught on quickly.

“I’m not lying to you: Within a week, Fernando was throwing the screwball as good as Babo,” Brito told The Times in 2011, using Castillo’s nickname.

With an expanded arsenal, Valenzuela thrived with the Dodgers’ Double-A affiliate in San Antonio in 1980. The left-hander won 13 games and tossed 11 complete games while striking out a Texas League-best 162 batters in 174 innings.

Valenzuela was called up in September when rosters expanded and he appeared in his first game for the Dodgers on Sept. 15, 1980, when he pitched two innings in a 9-0 loss to the Braves in Atlanta. He allowed two unearned runs and recorded his first MLB strikeout, fanning Jerry Royster.

“The only Dodger performance worth noting was by pitcher Fernando Valenzuela, who made his major league debut,” The Times wrote after the game.

Thrust into a pennant race, Valenzuela appeared in 10 games and gave up no earned runs in 17⅔ innings as the Dodgers forged a tie atop the NL West with the Houston Astros at the end of the regular season. Faced with a one-game playoff at Dodger Stadium, manager Tommy Lasorda elected to start Dave Goltz — a high-priced right-hander the team had signed before the season but who had performed poorly — over Valenzuela, then 19 years old, who had pitched two innings the day before.

Goltz lasted three innings, giving up four runs in a 7-1 loss as the Dodgers’ season came to an end. Valenzuela, for his part, pitched two scoreless innings and gave up one hit.

It was a hint of things to come, but once again, a confluence of events put Valenzuela in the spotlight.

Valenzuela was on the Dodgers roster coming out of spring training in 1981, firmly in the team’s starting pitching rotation behind left-hander Jerry Reuss and right-hander Burt Hooton. The day before the season opener against the Astros at Dodger Stadium, Reuss suffered a calf injury during a team workout. Hooton and other starting pitchers were not ready to step in, allowing Valenzuela to become the first rookie pitcher to start on opening day in Dodgers history.

“Tommy liked to make jokes, so I said ‘hahaha,’” Valenzuela said about being informed of the assignment. “And he said, ‘it’s not a joke, it’s serious.’ And that’s when I said, ‘yeah, why not?’”

Valenzuela scattered five hits, went nine innings and defeated the Astros, 2-0, to kick off a remarkable display of pitching that captured the imagination of baseball fans and quickly became a source of pride for Mexicans and Mexican Americans. He went the distance again in his next start, a 7-1 victory over the Giants in San Francisco.

Then came three more shutouts — at San Diego, at Houston and at home against the Giants — before he pitched another complete game and beat the Expos 6-1. Then another shutout at New York against the Mets before a 3-2 win at home against the Expos to cap off an 8-0 start that featured a 0.50 ERA.

By this point, the buzz and attention surrounding the portly left-hander had reached a fever pitch, and the impact was as wide as it was sudden.

The Dodgers, who had broadcast games in Spanish since 1959, saw a ratings increase and interest in expanding their radio network into Mexico. Jarrín, the team’s lead play-by-play announcer, was thrust into the spotlight himself, serving as an interpreter for Valenzuela during news conferences before and after games.

“To the point that, in those years, the radio station ratings were usually 3.4,” Jarrín said in 2021. “We were happy with 3.4. But at KTNQ, we’d get a rating of 8.6. Never had a radio station done that before. It was because of Fernando, Fernandomania and the Dodgers.”

L.A.’s Mexican community began to flock to Dodger Stadium during his starts. The Dodgers, who had become the first franchise to draw 3 million fans in 1978, averaged 48,430 fans during Valenzuela’s home starts and 42,523 overall during the strike-interrupted 1981 season — the highest average attendance in Dodger Stadium history to that point.

“It was like an East L.A. backyard party,” boxing historian and author Gene Aguilera told The Times in 2021.“He was like a family member you would visit every four days at Dodger Stadium.”

The electric atmosphere was also surprising considering the fraught history at Chavez Ravine, when Latino families were uprooted from neighborhoods there throughout the 1950’s to eventually clear the way for the construction of Dodger Stadium. L.A.’s Latino community never forgot that chapter in the city’s history, but Valenzuela’s meteoric rise and everyman appeal proved hard to resist.

“Fernando was really key for bringing the hearts and minds of la raza to the stadium,” Richard Montoya, a filmmaker and playwright who staged a show about the history of Chavez Ravine, told The Times in 2021.

Added Richard Santillán, a professor emeritus and longtime season-ticket holder: “People laughed, my father laughed. My father would say he looks just like a typical mexicano. He was pudgy … he was what they’d call gordito.”

Though a 50-day strike wiped out two months of the 1981 season, Valenzuela continued to achieve milestones through the rest of the year — the second rookie pitcher to start an All-Star Game, the first rookie to lead the NL in strikeouts, a World Series championship, a Cy Young Award, a Silver Slugger Award, to name a few.

Valenzuela remained a consistent top-line starting pitcher over the next four seasons, averaging nearly 16 wins. Before the 1983 season, Valenzuela also became the first player to win a $1-million salary in arbitration — with his representatives using Valenzuela’s vast drawing power as part of their argument.

The year 1986 proved to be fruitful on several fronts for Valenzuela. In February, the Dodgers signed the left-hander to a three-year contract worth $5.5 million, the largest for an MLB pitcher at the time. In July, he tied a record by striking out five consecutive batters in the All-Star Game — a mark set in 1934 by Carl Hubbell, himself a screwball pitcher.

Despite the Dodgers finishing 73-89, Valenzuela won 21 games to lead the NL and pitched 20 complete games to lead all of baseball — numbers unheard of in MLB today.

By this point, Valenzuela was firmly a cult hero among Mexicans and Mexican Americans. Latino artists wrote songs in his honor and painted murals of Valenzuela, and he was referenced in the 1987 comedic film “Born in East L.A.” He was mobbed whenever he made personal appearances in East Los Angeles at parks and schools.

Through his first six seasons, Valenzuela won 97 games, threw 84 complete games and posted a 2.97 ERA while never landing on the injured list. But despite being only 25 years old at the end of the 1986 season, he did not maintain that form for the rest of his career as injuries and wear and tear from overuse set in.

Valenzuela won 29 games during the next three seasons and was left off the postseason roster in 1988 as the Dodgers stormed to another World Series title.

In what turned out to be his final season with the Dodgers, Valenzuela provided fans one last thrill on June 29, 1990. Earlier in the day, Dave Stewart — Valenzuela’s former teammate on the 1981 championship team — threw a no-hitter for the Oakland Athletics in Toronto. Watching on television in the clubhouse before his start at Dodger Stadium, Valenzuela turned to some teammates and said, “That’s great, now maybe we’ll see another no-hitter.”

And Valenzuela delivered, beating the Cardinals 6-0 to mark the first time in modern baseball history that two no-hitters were thrown on the same day. The final two outs came when he induced Pedro Guerrero, another former teammate on the 1981 team, to ground into a double play.

He finished the 1990 season 13-13 with a 4.59 ERA — his final win with the Dodgers coming on Sept. 14 at Cincinnati, a 155-pitch complete game. The end of his tenure with the Dodgers came bitterly and abruptly the following March, when the team released him on the eve of the 1991 season — on the day his $2.55-million contract would have become guaranteed.

Earlier in spring training, the Dodgers had played a pair of exhibition games in Monterrey, Mexico — providing the 30-year-old Valenzuela an opportunity to pitch in his home country for the first time in his MLB career. Even 10 years removed from the initial wave of Fernandomania, Valenzuela remained the star attraction.

“We knew Fernando’s importance to his country before we came down here, but to see it, to feel, to hear it … it was an extraordinary moment,” former Dodgers owner Peter O’Malley said at the time.

Nevertheless, citing his ineffectiveness during spring training and his 23-26 record the previous two seasons, the Dodgers elected to move on, which upset and surprised Latino communities across the Southland.

“He gave them everything he had,” one fan, Raul Montesinos, told The Times. “It’s like a worker when he’s all used up and the boss gets rid of him because he’s of no use anymore.”

Valenzuela vowed to continue pitching, signing with the Angels in May 1991 but lasting only two starts before being released later that season. After a year pitching in the Mexican league, Valenzuela returned to the majors in 1993 and pitched for the Baltimore Orioles, Philadelphia Phillies, San Diego Padres and St. Louis Cardinals over the next five seasons. His best campaign was in 1996, when he won 13 games for a team that won the National League West division.

After being traded to the Cardinals in June 1997 and then released by them a month later, he never pitched in the majors again. Valenzuela was invited to spring training by the Dodgers in 1999, an offer he declined. Over 17 seasons in MLB, 11 with the Dodgers, Valenzuela won 173 games. (He ranks ninth on the Dodgers’ career wins list with 141.)

By 2003, the relationship between Valenzuela and the Dodgers thawed enough that he joined the team’s Spanish-language broadcast team, helping call games with Pepe Yñiguez and Jarrín, the man who’d been by his side during the heady days of Fernandomania. Valenzuela was part of the broadcast team through this season before stepping away from the booth in September to focus on his health, the Dodgers said at the time.

The broadcast booth was an avenue that allowed Valenzuela to maintain a high — but guarded — profile, though he remained visible in other ways. He helped coach the Mexican national team in the World Baseball Classic four times between 2006 and 2017; he became a U.S. citizen in July 2015, going through the naturalization ceremony at the L.A. Convention Center, about three and a half miles from Dodger Stadium; he headed an ownership group that purchased the Quintana Roo Tigres, a Mexican League team located in Cancun, in 2017; and in 2019, the Mexican League retired his No. 34 jersey.

That number had never been worn by any Dodger since the team released him in 1991, an unofficial acknowledgment of his effect on the franchise. But the Dodgers steadfastly stood by their policy of retiring only the numbers of players who were already in the Baseball Hall of Fame (though Jim Gilliam’s number was retired in the wake of his death in October 1978).

And Valenzuela, despite his impressive run early in his career, did not garner enough support for enshrinement (75% of the vote from members of the Baseball Writers Assn. of America is needed). In his first year on the ballot in 2003, he netted 6.2% of the vote, surpassing the 5% threshold needed to stay on the ballot for another year. The number dropped to 3.8% in 2004 and he fell off the ballot in subsequent years.

But Valenzuela’s enduring legacy, with the Dodgers and its fans, and the sport as a whole, provided an opportunity to retire his number on Aug. 11, 2023, in a pregame ceremony at Dodger Stadium.

“It never crossed my mind that this would ever happen,” Valenzuela said before the ceremony. “Like being in the World Series my rookie year, I never thought that would happen. I didn’t think this would happen, because first of all you have to be in Cooperstown. It really caught me by surprise. It’s hard to put into words what this means.”