The pop star Robbie Williams is leagues more famous in his homeland of England than here in the States, American tastemakers having capriciously chosen to ignore his chart-topping ’90s boy band Take That and megawatt solo career. Go see his biopic anyway. All you need to know heading into “Better Man” is that Williams considers himself a performing monkey. Some screenings even have a pretaped introduction where he tells you so himself.

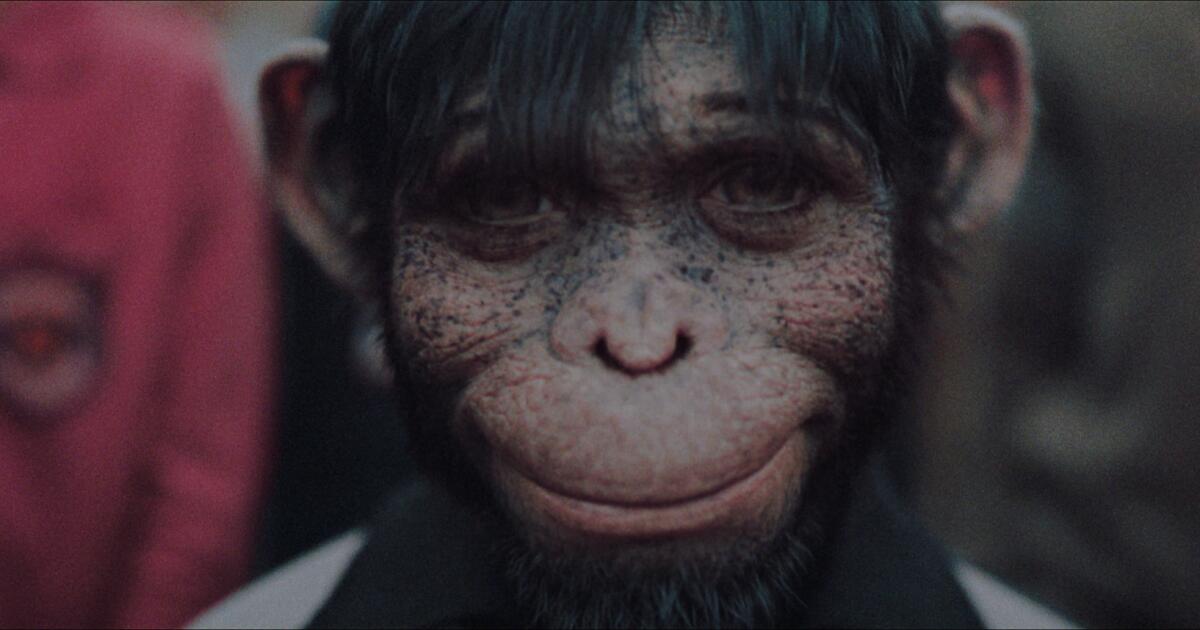

The wildly creative director Michael Gracey (“The Greatest Showman”) fills you in on the rest with hilarious, no-holds-barred zeal: the drugs, the tabloid love affairs, the insecurity that made Williams desperate to be famous — a need to entertain that rewarded him with 14 No. 1 albums on the UK charts and a Guinness world record for selling 1.6 million concert tickets in 24 hours, as well as exhaustion and rehab. Through it all, the infamous party animal is played by a CGI chimpanzee. As Williams the monkey admits to his support group, “I’m unevolved.”

Willams produces and narrates the film and seems to have given the screenwriters Simon Gleeson, Oliver Cole and Gracey the go-ahead to rip him to shreds. Some superstars hide their megalomania under humility; Williams shields his tenderness with jokes about being a narcissist, only exposing his wounds in his muscular, vulnerable lyrics. He insults himself in the first minute of the movie, and from then on wears his humiliations like a Purple Heart pinned to his hairy, simian chest.

It’s conceivable that the guy who titled his best-of album “The Ego has Landed” approved the chimpanzee gimmick because he simply couldn’t bear the idea of a casting director discovering a younger version of Robbie Williams. And it’s easy to accept the conceit. Both chimps and pop stars are prone to destroying furniture and grinning while ripping off your face. Even physically, Williams shares an ape’s frank gaze and defiant chin. He charges instinctively after what he wants, chiefly a crowd so deafening he can’t hear his own self-loathing.

Here, Williams acknowledges his struggles with depression. But his goal is the same as ever: Entertain at all costs. That’s been his modus operandi — a defense mechanism, really — since he was a 16-year-old, terrified that he was the least-talented and most-replaceable member of Take That, the biggest teenybopper pop act in Britain at the time. By moxie alone, he became Take That’s fan favorite, the cheeky one who would do anything for applause. Baring his bum on TV, Williams is the embodiment of the phrase “charm offensive.”

Yes, there are the beats you expect in a musician’s biopic: the scene where he quits the band, the song lyrics scribbled after a tragedy, the wrenching quest for validation from his absent father, Peter (Steve Pemberton, fantastic). If you could tear your eyes away from the screen enough to check a stopwatch, not one minute goes by without a flourish that’s either funny, ridiculous, stunning or emotional. Sometimes, they’re all at once, like when young Williams (played by Carter J. Murphy), mimics his dad, a two-bit club performer, as they sing along with Frank Sinatra on television. The moment is at once a lens into a power dynamic that will run the length of the film, and a send-up of monkey see, monkey do.

Jonno Davies is the ape performer under the Wētā FX motion capture and he’s terrific, as is the ensemble who acts against him with spectacular conviction. His Williams is always in motion: winking, gyrating, climbing in people’s laps. Millions of people watched the awards shows where Williams waggled his hips at Tom Jones, or challenged Oasis’ Liam Gallagher to a fist fight — moments that have been absorbed into pop culture. Williams was loose and free and likely blitzed out of his mind. Davies, however, nails it sober.

It’s unclear how much of the dance choreography Davies is doing under those pixels. He’s a proper theater actor who came to renown playing Alex in an onstage production of “A Clockwork Orange.” There’s a rousing musical sequence where the Take That lads rampage through the West End and, at the song’s peak, Williams leaps from the top of a double-decker red bus. Like everything in the movie, this heavily digitized fabulosity is all vibes — the gleeful mayhem of being rich and famous and 20 years old. The other four actors in the scene playing the human members of the band are fully exposed and great at both dancing and self-mockery. Jake Simmance, as songwriter Gary Barlow, gets one of the film’s biggest laughs. Incensed that Williams is falling down drunk at a stadium show, his Barlow flounces up in a thong to hiss, “You’re making us look like fools out there!”

The script toys with our awareness that pretty much everyone Williams feuded with is still alive — even his dad — and some, including Nigel Martin-Smith, the founder of Take That, have proven to be litigious. Fittingly, the humor bobs and weaves, setting up punchlines only to pivot to a zinger. Nigel, Williams says, is “an absolute sweetheart.” Cue a pause long enough to make you wonder if he’ll leave it there or drop the hammer. (He drops it, over and over.) For a bonus dig at the dawn of the grunge era, the hair and makeup team give Nigel (Damon Herriman) an icky, trendy chin-strap goatee.

As for Williams’ fans, they’re seen as equal parts thrilling and terrifying. After he leaves Take That in 1995, suicide hotlines are flooded with calls from sobbing girls. Here, during a nightmarish underwater rendition of his ballad “Come Undone,” those teenagers swirl around him like frenzied chum, their slashed wrists trailing blood as they threaten to sink him, too. The only thing scarier would be going ignored, a dilemma Williams satirized in his 2000 music video “Rock DJ” which, if you weren’t scarred by it at the time, climaxes with Williams impressing a room of women by cheerfully peeling off his own skin and pelting the crowd with chunks of his raw flesh.

Audiences who know his hits will see them gorgeously recontextualized as needed to suit his life story — the chronology of his singles doesn’t matter at all. In these mini-music videos, Gracey and his five-person editing team merge the present and future to cover as much ground as they can. The standout is the love song “She’s the One,” which starts with Williams meeting his early girlfriend, All Saints’ Nicole Appleton (Raechelle Banno), on a yacht. As the fledgling couple whirls into a ballet, the number flashes forward to show the heartbreak ahead, and then cuts back again so that we feel the sting of all that wasted promise.

There’s no need for the movie to look this good. Erik A. Wilson’s cinematography is warm and grainy; it and the script have been polished until the scene transitions flow like vodka down a frat party’s ice luge. Gracey gets an astonishing amount across in the details: the goofy creak of a leather jumpsuit, a camera angle tilted to show the utterly unspectacular pulley system that yanked Williams upside-down in front of a crowd of 125,000. The production designers are always pulling the rug out from under us. As soon as Williams ascends to a new height of fame, it begins to look tatty. There’s always someplace cooler he’s got to get to next.

Yet, even as the movie captures Williams’ recklessness, it’s also a convincing sketch of his artistic growth and commitment. We catch on that he’s a genuine songwriter before he does. There’s a moment where his new manager (Anthony Hayes) warns Williams that success will drain him of everything he’s got, and then the film launches into an exhausting montage of cocaine and crowds and puke that proves him right. So it says something about American hardheadedness that we’ve resisted learning about Robbie Williams for the last 35 years. We’re as stubborn as he is. But go to the movie anyway. Within two hours, you’ll be so caught up in his charismatic maelstrom that when one chimpanzee tearfully stabs a baby chimpanzee on a confetti-ed battlefield, that you’ll think, yes Robbie, I totally understand where you’re coming from.