Violent, traumatizing scenes flash on the screen — battles, bullets, children being cradled, people fleeing from Vietnam to refuge in America — as “New Wave,” the documentary, opens. These are the horrors of war as we’ve so often seen them.

But unusually, danceable beats and hypnotic synths invade the archival footage of the final days of Saigon, when the U.S. government swooped in to resettle more than 120,000 refugees airlifted to military bases in 1975, rescuing them after bloodshed that left lives still ravaged today.

Filmmaker Elizabeth Ai, pregnant during the conception of the project, had been “grasping at straws” for how she would highlight stories about her ancestral inheritance for her unborn baby. Then she remembered some familiar tunes. “As a child of the ’80s, I was obsessed with the teenagers who raised me — my parents were out of the picture and these teens, my uncles and aunts, stepped in.

“When I was thinking of what I would share with my daughter,” Ai says, “new wave music popped into my head — the music was an anchor to some of my earliest and fondest memories. Also, everything most Americans knew about the Vietnamese experience started and ended with violent Vietnam War movies or ghettoized versions of us. I figured it was time to flip the script and focus on a subculture that so few knew about.”

And so “New Wave” was born. The film will screen at Laemmle Glendale from Friday through Oct. 31.

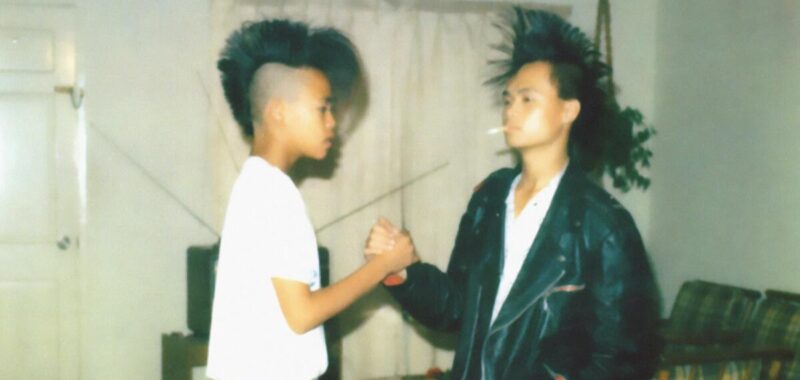

Expect mile-high hair. Cheesy tracks. Youth rebellion. Ai went on a mission to excavate an untold story of punks in the chaotic world of Vietnamese New Wave, one that led her to a deeper cultural truth.

“The people who came before me were always on the run,” the director says in a narration that accompanies the film’s beginning. In an interview via Zoom, Ai, 44, likens refugees to “escape artists.” As she dug into the existence of her family members and icons of the New Wave scene — not the MTV-ready icons most Americans know such as Blondie or Billy Idol, but a separate echelon of Vietnamese artists — she discovered a tapestry of broken dreams and unmet expectations beneath the surface. She describes them as “not just fleeting moments of teenage rebellion, but acts of defiance against the lingering shadows of war and the sacrifices made by a generation trying to rebuild.”

“New Wave” juxtaposes the memories of Ai’s uncles and aunts sneaking into underground clubs around Southern California with impressions of her own fragmented childhood, scarred by parental abandonment. Ai worked on her directorial debut for six years before its world premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival last June.

Although the Vietnamese call this type of music “new wave,” the rest of the world calls it Eurodisco. The electronic drops, the punk-goth aesthetics, the sounds of keyboards and drum machines — such musical ingredients reflected a time of nostalgia as well as revolution.

“When I hear the word ‘refugee’ — it brings back all the memories that I don’t want to keep,” said Ian Nguyen, a DJ and concert producer who’s one of the film’s main interviewees. As a pioneer who spread the New Wave gospel by playing it for audiences back then and even now, he links its sounds as similar to Depeche Mode and OMD.

In the film, Nguyen takes viewers through his own fraught relationship with his father, the late Nguyen Mong Giac, among Vietnam’s famed writers, who tried to launch a more stable life in Orange County. He strongly disapproved of his son and his career.

Their differences play out against a backdrop of jerky, sensual rhythms and dark emotions. For the younger set like Nguyen, the music was part of a cultural evolution, an awakening that pushed them to be bolder, escape from traditional homes to crash in motel rooms and to barrel through romances. Yet to their elders, the souped-up noise was not any type of karaoke songs they would ever croon.

Ysa Le, executive director of the Viet Film Fest, where earlier this month “New Wave” had its West Coast premiere (winning the grand jury’s best feature award), says the documentary mesmerized her.

“It’s about family, about intergenerational trauma, and it’s a story we need to bring out,” she says. “It’s our journey and it will help many people to look at the conversations in the film between grandparents and parents and children and how we need to talk, before it’s too late.”

At the three-day film festival she founded in 2003, devoted crowds filled two sold-out Santa Ana theaters to catch the film, standing in long lines for Ai to autograph its companion book, “New Wave: Rebellion and Reinvention in the Vietnamese Diaspora,” published by Angel City Press and the Los Angeles Public Library. The hardcover packs in photos and essays from prominent Vietnamese scholars and stars.

One accountant in the throng clutched five copies, intending to mail the book to his nephews and nieces in the Midwest. Taylur Ngo, a writer from San Diego, emerged from the screening uplifted.

“I’m going to give it to the women filmmakers,” she says. “They are the ones looking to the family secrets. It’s them who are confronting family life and domestic life in a really nuanced and sensitive way. They aren’t afraid to question the matriarchy — or patriarchy — in a movie that’s beyond music.”

“I think it’s time for us to go inside households and capture what’s complex and hidden,” Ngo adds.

A mother of two, she says she has listened to New Wave‘s essential singers, though it was “a bit before my time. Yet I didn’t know about the rebellious side of it, and how it helped the 1.5 generation” — those who landed in a new country as a child or adolescent, yet have traits of both first- and second-generation immigrants — “come to terms with their identities.”

Among the pop idols of the New Wave movement, none were more eminent than Lynda Trang Đài, often labeled the “Vietnamese Madonna.” Writhing to her trademark “Jump in My Car” hit (“Jump in my car / Don’t be afraid / Only young heroes can never wait / You are my number one / Till the morning turns to dawn”), she electrified audiences.

Her provocative stage presence in a dazzling series of Paris by Night videos, her tight-fitting body suits and bikini tops, her bravado and sultry voice made the older generation gasp. Her performances ignited youth power, giving fans the catalyst to turn their backs on conventional Vietnamese customs. The public swarmed Đài’s shows clad in denim, leggings and neon tees, doused in Aqua Net.

“I guess I was destined to be a New Wave singer — and to be a big part of it. That’s my whole career,” Đài, 56, says by phone, on break from Lynda Sandwich, the popular Westminster baguette restaurant she runs. “The music is so, so special because it captured a period of time when Vietnamese Americans had made it with music in America. There was joy. There was regret. There was the fashion and cars that went along with it.

“You have to remember that in ’75, when people just came, we didn’t have anything to choose from. They just listened to the traditional Vietnamese songs.”

Enter Đài, Tommy Ngô (her husband), Trizzie Phương Trinh, Tuấn Anh and more. As the New Wave brand grew, along with VHS tape sales, so did California’s Little Saigon entertainment and cultural hub behind it.

“Yes, there was displacement and trauma, but they made music — they had fun. This was my homage to the people that raised me,” Ai says. “I only get one chance to make my first movie and I really want to say something. That was when the real excavation began.”

To an enthralled generation, the genre’s music has never died — a tribute to the longing for belonging, still not erased.