Wildfires that forced thousands to evacuate and destroyed hundreds of homes and other structures; heat waves that smothered the Southwest in sweltering, deadly heat for weeks on end; and hurricanes that have wrought catastrophic damage, nearly wiping away whole towns—these are just a few of the climate-change-fueled disasters that have taken hundreds of lives in the U.S. so far this year. Conservatively, such disasters cost the country $150 billion annually, and that is with just 1.1 degrees Celsius of warming since preindustrial times. No part of the country is immune to the effects.

Climate scientists are in clear agreement that in order to avoid ever-worsening disasters and disruptions to our societies, the world must rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The policies put in place over the next few years will determine what the future climate looks like and what threats the world will face. The U.S. is crucial to this effort. And in the 2024 presidential election contest between Vice President Kamala Harris and former president Donald Trump, voters have a choice between diametrically opposed visions of what the country must do. “When it comes to climate change, the contrast between Trump and Harris could not be more stark,” says Leah Stokes, a University of California, Santa Barbara, political scientist who focuses on energy and climate.

Over the past four years, the Biden-Harris administration has taken by far the most action to address the climate crisis of any U.S. presidential administration—primarily through enacting the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), for which Harris cast the tiebreaking vote. The administration has also strengthened many environmental regulations and made environmental justice a key goal. During her speech in which she accepted the Democratic nomination for the presidential race, Harris said people in the U.S. deserve “the freedom to breathe clean air and drink clean water and live free from the pollution that fuels the climate crisis.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Trump has stated that he wants clean air and water—but his administration rolled back more than 200 environmental regulations. He has appointed Supreme Court justices who overturned decades of wetland protections and weakened the role of science in government policymaking. And the plans laid out under the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 (widely considered a blueprint for a second Trump administration) would seek to build on that deregulation, maximize fossil-fuel production and dismantle much of the government’s climate science apparatus. Although the Trump campaign has tried to distance itself from Project 2025, many former Trump officials helped draft it. And in 2018 the Heritage Foundation trumpeted that the then-sitting Trump administration had adopted nearly two thirds of the conservative think tank’s policy recommendations. Trump has also said that he would rescind unspent IRA funds and that climate change is “not our problem.” But the U.S. is the largest historical contributor to global warming, and abundant research shows that climate change is worsening extreme weather disasters here and elsewhere. “Any way you slice it, it is firmly the U.S.’s problem,” says Robbie Orvis, senior director of modeling and analysis at Energy Innovation (EI), a nonpartisan energy and climate policy think tank. “You can’t put up a wall for climate.”

Climate Policies Past and Present

By far the biggest signature climate initiative of the Biden-Harris administration is the IRA, which pledged $369 billion in climate investments over 10 years. Adding to that are climate-related provisions in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the CHIPS and Science Act. There are also major new Environmental Protection Agency regulations that target carbon dioxide emissions from power plants, methane pollution from the oil and gas industry, and vehicle tailpipe emissions. This policy push is “more than doubling the annual pace of emissions reductions this decade compared to the rate achieved in the 2010s,” according to an EI report.

With the added investment, tax incentives and continued declines in costs, renewable energy and battery storage have dominated new electricity generation projects in the U.S. in the last couple of years. Electric vehicle sales reached record levels in 2023. But oil and gas production have also reached record highs during both the Trump and Biden-Harris administrations, and the U.S. is the world’s top natural gas exporter.

It is unclear exactly where Harris stands on the question of U.S. fossil-fuel production, though she has spoken about the need for a mix of energy sources and said she no longer supports a ban on fracking. Stokes notes that Trump, on the other hand, has said that on day one, he wants to begin to “drill, drill, drill,” and the Washington Post reported that when meeting with oil executives this spring, Trump said he would immediately reverse a number of environmental policies if they raised $1 billion to help him get reelected. Project 2025 also calls for cutting government research into clean energy technologies and maximizing fossil-fuel extraction on federal lands.

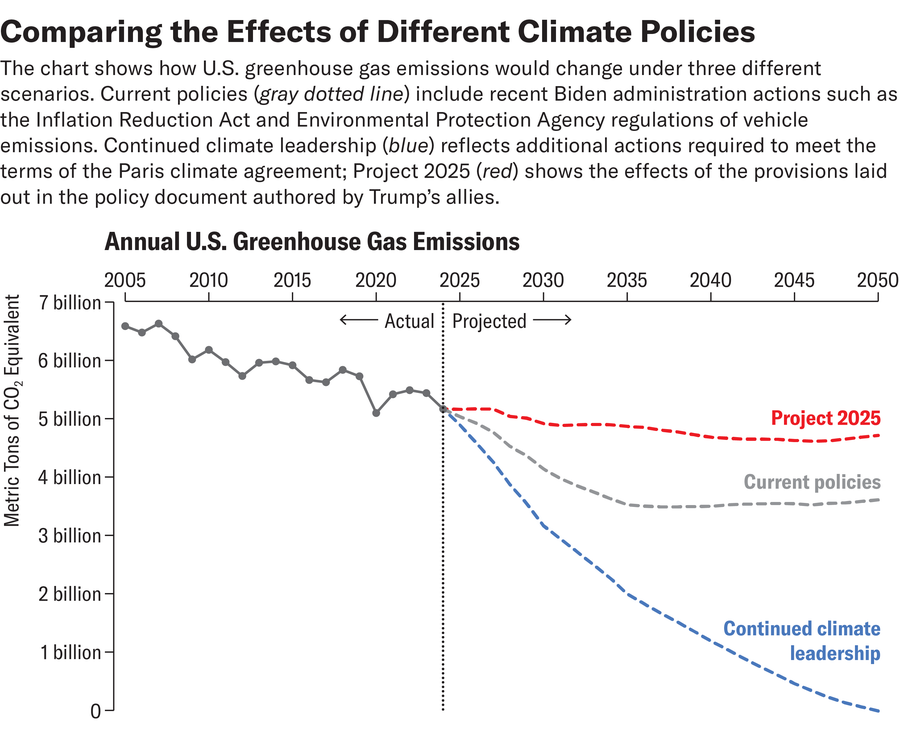

To provide a broad look at how potential policies under Harris or Trump would shape future U.S. emissions, Orvis’s team at EI used its Energy Policy Simulator, an open-source computer model. The researchers compared current policies under the Biden-Harris administration with more ambitious policies that achieve a target of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 and with the policies laid out in Project 2025. They found that the latter scenario “basically stops the progress that’s been made,” Orvis says. And even if current policies aren’t enough to meet international climate goals, any progress that can be made is crucial because “each tenth of a degree [of warming] is more damaging than the previous one.”

Amanda Montañez; Source: Energy Innovation Policy & Technology

And jettisoning IRA provisions and other Biden climate policies wouldn’t just impact emissions. “We’re clearly in the middle of a large manufacturing renaissance in the U.S.,” Orvis says, and this is partly because IRA incentives made it competitive for clean energy companies to be built here. Scrapping those incentives could mean that companies would take hundreds of billions of dollars in investments—and the jobs that come with them—to other countries. Such action would “permanently exclude the U.S. from being a clean energy manufacturer and exporter because the ship will have sailed in the next few years,” Orvis says. Continued fossil-fuel extraction and use in power generation would also increase household energy costs, the EI report found.

Trump’s running mate, J.D. Vance, has decried the IRA and said a Trump administration would undo it. But during the recent vice presidential debate, he said tackling climate change would require bringing back “as much American manufacturing as possible, and you’d want to produce as much energy as possible in the United States of America.” But “that is exactly what the Inflation Reduction Act is doing,” Orvis says. “Eliminating that would be disastrous for those industries.”

Though Harris has not laid out specific climate and energy plans, Stokes and Costa Samaras, director of the Carnegie Mellon University Scott Institute for Energy Innovation, point to her proposed policy to incentivize building more affordable housing (particularly multifamily dwellings such as apartment buildings). “There’s a lot of the greenhouse gas emissions in the economy that are wrapped up into where people live,” Samaras says. If built nearer to urban centers or closer to public transportation routes, that could mean more people can take trains or buses to work instead of driving, for example. “Housing policy is climate policy,” says Samaras, who also worked for the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy until this year.

Disaster Preparedness and Response

Regardless of who wins, the next president will have to deal with the consequences of climate change. Disasters such as hurricanes, floods and heat waves will continue to strike the country with increasing frequency and severity.

The Biden-Harris administration has emphasized climate resilience and preparing communities to better withstand disasters, and it launched an initiative to provide states with money to improve building codes. The IRA and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law “are also giant climate resilience laws, the biggest in history,” Samaras says. And Harris has decried misinformation that Trump has spread around the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)’s response to Hurricanes Helene and Milton.

The Project 2025 plan, in contrast, calls for slashing funding to disaster response, ending disaster preparedness grants and doing away with the National Flood Insurance Program. The latter is the only way that many people in the U.S. can afford flood insurance, which is not covered by standard homeowners’ policies because private insurers fear the high risks of incurring major costs. And during his first administration, Trump refused to approve disaster aid to areas hit by California wildfires until staffers showed him that those areas had voted for him, multiple staffers told POLITICO’s E&E News. Presidential budget requests made during Trump’s first term also included major cuts to FEMA, including for repairing high-risk dams and creating flood maps.

Project 2025 calls for stripping the National Weather Service of its forecasting duties, which would relegate it to data collection, and shifting forecasting to private companies. The plan would effectively replace a single, central warning system with a patchwork of apps and websites that users might have to pay to access. “It’s inequitable,” Samaras says. “It’s bad science. It’s going to cost people’s lives.”

For climate experts like Samaras, Stokes and Orvis, the choice in this election on the climate front is clear—because, as Samaras says, “Every year matters. Every ton [of CO2] matters. Every action matters.”