Much like the fight for the White House and the Senate, the battle for control of the House is especially tight — but it is being played on a field tilted decisively toward the GOP.

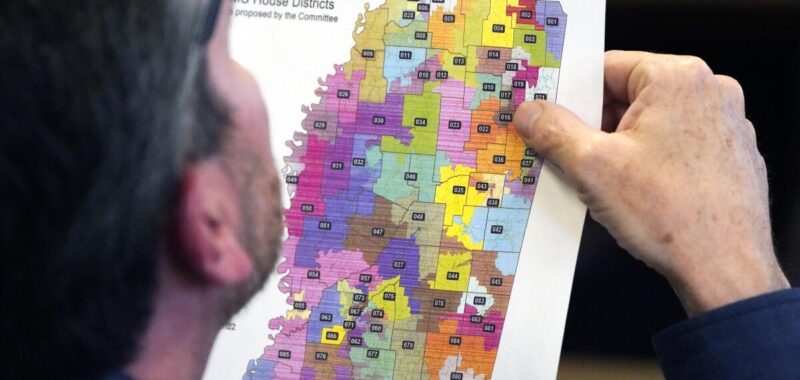

That’s no accident. Republicans designed the field itself. There are 435 House districts. The GOP drew 191 of them, the Democrats just 75. (The rest were created by courts, commissions or divided governments; seven states have just one House member and elect statewide.)

It doesn’t get mentioned enough by the media, which focuses on the horse race of how either side might reach 218 seats. Yet in a race this close, partisan gerrymandering will be central to determining which party takes control of the House. And as it has since 2012, the GOP begins with a head start.

Just as importantly, there are dangerously few competitive seats remaining. Thanks to a 2019 Supreme Court decision that declared partisan gerrymandering a political issue that the federal courts could not decide, the national congressional map has been maximally gerrymandered almost everywhere it is possible.

The Cook Political Report has identified only 25 tossups out of 435 seats. Sixteen of those were drawn by courts or commissions, which means only nine seats drawn by politicians nationwide remain competitive. Cook finds an additional 18 seats with just a small partisan lean one way or another, but classifying those as competitive requires straining to believe Montana will elect its first Democrat since the 1990s, or Connecticut will have its first GOP winner since the mid-2000s.

Gerrymandering is not new, but it works better than ever before. In decades past, the advantages that flowed from creating a Democratic-leaning or Republican-friendly district tended to erode between one census and the next through demographic and political changes. However, today’s sophisticated map-making software and voluminous voter data have proved all but impossible to overcome — and Republicans’ use of such data could tilt control of Washington once more.

That GOP advantage has only widened this year. Republicans will likely gain four seats in North Carolina through an extreme gerrymander that is new this cycle. State courts can intervene in redistricting, and two years ago, North Carolina’s Supreme Court ordered a congressional map with no undue partisan edge; it produced a balanced 7-7 delegation from this purple state.

When the GOP captured the state court in 2022, judges almost immediately reversed that decision and freed the gerrymandered state legislature to draw a new map that is likely to produce 11 Republicans and three Democrats. That’s 79% of the delegation even as polls show a potential Democratic sweep of statewide offices and a tight presidential race.

Blue New York also has a new map this fall, but even though some partisans hoped to counteract North Carolina’s changes, lawmakers actually did little to alter a court-drawn map from 2022. But Democrats did not enact an egregious map, and the partisan balance did not change more than a percentage point in any other district, largely preserving a balanced map that produced a proportional 16-10 Democratic delegation in 2022.

Federal courts helped unwind three GOP racial gerrymanders in the South as Voting Rights Act violations. Democrats will likely gain a seat in Alabama and Louisiana as a result of new majority-Black districts; in Georgia, however, the GOP created a new Black district but dismantled a different blue seat, likely preserving the existing 9-5 edge.

Much of the existing GOP bias — such as the 6-2 delegation from closely divided Wisconsin — remains from redistricting after the 2010 census. Republican campaigns and groups targeted control of just over 100 state legislative seats that year in Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, North Carolina and other states, while Democrats snoozed. (In 2012, Democratic candidates won 1.4 million more votes nationwide, but the GOP won 234 seats to 201 for the Democrats.)

Then during the 2021 cycle, following the Supreme Court’s abdication, both parties looked to lock in every advantage they could. Republicans controlled more states thanks to previous gerrymanders, and had more opportunity. Democrats worked around the margins, adding three seats in Illinois and awarding themselves an extra seat in Oregon and another in New Mexico.

Republicans stole most of that back in Florida alone, nabbing an additional four seats. They added seats in Texas, grabbed one in Tennessee by cracking blue Nashville in half and dividing it among two red districts, and wiped competitive seats in Salt Lake City, Oklahoma City and Indianapolis off the map.

In Ohio, the state Supreme Court twice declared the GOP’s maps unconstitutional, but lawmakers defiantly disobeyed a court order, ran out the clock and enacted them anyway. In Arizona, a brazen GOP long game to pack the state’s ostensibly independent commission with partisans helped flip a 5-4 Democratic delegation into a 6-3 GOP edge in 2022, even while voters elected a Democratic governor and U.S. senator. Similar hardball with Iowa’s famously nonpartisan commission helped Republicans claim one additional seat.

This is not to say the Democrats cannot regain control of the House. Reforms in Michigan and Virginia have created a fairer playing field, as have court orders in Maryland and divided government in Pennsylvania. Nonetheless, victory for the Democrats would require drawing an inside straight from a rigged deck. Republicans hold more options for retaining their majority.

Yet there may be an even bigger issue than partisan control of the House at stake this year. State legislatures in otherwise competitive battlegrounds such as Wisconsin and Georgia are as gerrymandered as the congressional maps. Uncompetitive districts in those legislatures have produced extreme caucuses of election deniers who — if they don’t like the results of the presidential election — could sow chaos before the electoral college meets in mid-December.

Imagine they’re successful in stalling certifications and pushing the presidential decision into the U.S. House for a “contingent election” as outlined in the 12th Amendment. Each state delegation would get one vote. Although Kamala Harris could carry the popular vote in Wisconsin, Arizona and Georgia, those states’ gerrymandered congressional delegations would likely vote along partisan lines for Donald Trump. If this constitutional nightmare scenario takes place, it too will be the result of toxic partisan gerrymandering that has wreaked unrepresentative extremes on our politics and might still tighten its toxic grip for many years to come.

David Daley, a senior fellow at FairVote, is the author of “Antidemocratic: Inside The Far Right’s 50-Year Plot to Control American Elections” and “Ratf**ked: Why Your Vote Doesn’t Count.”