“Kill Move Paradise,” a 2017 play by James Ijames, has the feeling of a devised work created in response to an urgent social crisis. Unlike “Fat Ham,” his Pulitzer Prize-winning Black American riff on “Hamlet,” this earlier piece has a loose spontaneity that makes it more dependent on the imaginative contributions of its interpreters.

This production, which opened Saturday at the Odyssey Theatre under the direction of Gregg T. Daniel, doesn’t make the most effective case for the script. There’s no denying the communal passion and commitment involved, but the artistry seems secondary to the activism.

The “Twilight Zone” setting is a waiting room in the afterlife. One by one, four black men find themselves inexplicably transported to a world that resembles some half-baked new video game that hasn’t yet worked out all the kinks.

Isa (Ulato Sam) is the first to arrive and he seems to be making a return visit. He is followed by Grif (Jonathan P. Sims), a former high school valedictorian who in time will recall an innocent traffic mistake with horrifically disproportionate consequences. Daz (Ahkei Togun), outwardly aggressive but inwardly soft, doesn’t appear to be breathing when he first arrives. Once revived, he puts up an intense fight for his personal freedom. Last to materialize is the youngest, Tiny (Cedric Joe), holding a toy gun and remembering only that he saw a friend shot down in the park, not realizing yet that he himself was the victim.

The geography of the space is a puzzle. The men understand nothing of their new situation and must learn the rules through trial and error. It’s a frustrating experience for them and, to a degree, for the audience, who would like the work to settle into a definable groove.

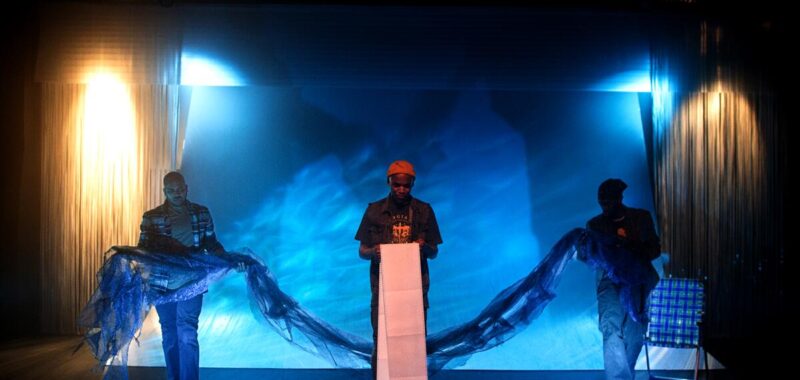

Scenic designer Stephanie Kerley Schwartz has envisioned what looks at first glance to be an indoor skate park. A makeshift back wall curves up at the back of the set like a giant wave. The characters try to climb their way out, flinging themselves up and flailing about violently as they slide down. There is no exit from this playwriting purgatory.

When the characters grope for a secret passageway, they receive an electric shock. The audience is visible to the characters. Who are these onlookers? A “representative slice” of America, Isa explains to Grif. Over time they come to understand that what happened to them must be witnessed before they can move on.

Questions about this limbo abound, but the play often seems to be coming up with answers on the fly. Stage metaphors work best when they’re treated as facts. Winnie, buried in a mound, doesn’t justify her plant-like state in Samuel Beckett’s “Happy Days.” She inhabits her plight as yet another unasked-for reality, no more ludicrous than our own. The figures of “Kill Move Paradise” have reason to reject their involuntary displacement, but they seem equally outraged over their theatrical conditions.

Isa reads from a book that provides instructions on how the men should proceed, but it’s a cryptic guidebook. The social justice crisis, however, that has brought them together doesn’t require too much guesswork.

An old printer (could God still be using what looks like a dot matrix?) spits out the names of Black folks with one thing in common — they are victims of a toxic combination of lethal violence and racial injustice. Some of these names made national headlines: Amadou Diallo, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland, among them. George Floyd, killed by police officers in 2020, has been added to what, tragically, is a club that seems to be ever-expanding its rolls.

This recitation of names creates a powerful ritual. Choreographer Toran Xavier Moore enhances the effect with ritualized dance moves. The sheer amount of time devoted to this segment is itself a condemnatory statement. How many people must die before reform is implemented?

A reenactment of Tiny’s murder allows “Kill Move Paradise” to move away from words to physical theater. A child’s game of blasting aliens with a toy gun is relived as it played out in Tiny’s imagination. How this recreational activity became a scene of literal bloodshed bonds the four characters not just as “martyrs” or “sacrifices,” but also as potential “saviors.” A redemptive brotherhood is formed.

The actors bring distinctive individuality, but the teamwork doesn’t build. This 80-minute piece sputters. A stronger emphasis on music might have given the work more momentum. (Composer and sound designer David Gonzalez’s contribution seems unduly inhibited.) And it’s a missed opportunity that the audience doesn’t play a more active role in a piece with clear communal intent. “Kill Move Paradise” moves unsteadily as a stage poem, though there’s clearly more at stake than artistic finesse.