Three generations of women are assembled in Sara Porkalob’s “Dragon Lady,” the first in her three-part series of musicals about what she refers to as her “Filipina American gangster family.” She’s not exaggerating. When baby Maria comes crying home after being bullied by a neighbor, her mother hands her a golf club and tells her to go back over there and kill the kid.

She’s not kidding, either.

The show, which opened Thursday at the Geffen Playhouse’s Gil Cates Theater under the direction of Andrew Russell, takes place on Maria Porkalob Senior’s 60th birthday. She and her daughter Maria have had a strained relationship predating even the golf club incident. Feeling unfairly judged as she approaches her golden years, Maria Sr. decides to share episodes of her harrowing life with her granddaughter Sara. What follows are scenes out of a movie melodrama — helpless poverty, horrific exploitation, routine brushes with violence and near-death escapes — performed under the guise of a karaoke cabaret.

Sara Porkalob starred in the 2022 Broadway revival of “1776,” directed by Jeffrey L. Page and Diane Paulus and featuring a multiracial cast made up entirely of female, transgender and nonbinary actors. The production was meant to view the musical through a 21st century, post-“Hamilton” lens, but Porkalob caused a stir in theater circles when she openly critiqued the handling of race and gender both in the rehearsal process and in the show itself.

That uncensored fearlessness, while not always appreciated in a team setting, is a valuable attribute in an artist creating her own material. Porkalob isn’t beholden to anything but her pursuit of the truth, which can be a dangerous game when delving into a family story marked by intergenerational trauma.

“Dragon Lady” moves back in time from the state of Washington to the Philippines, where we find Maria Sr. as a young girl, trying to survive the brutal murder of her father by a notorious gang. Working in the Red Dragon, a Manila nightclub owned by gangsters, Maria starts off as a cleaner, but as she matures into an attractive young woman she is promoted to singer. Promoted is a dubious choice of words, because the entertainers at the Red Dragon are expected to do whatever it takes to satisfy the customers.

Before she even knows what love is, Maria is swept off the stage by the boss of a ruling gang and impregnated. The story of her fight to keep her first daughter, whom she names Maria Elena, after herself, “her bittersweet joy,” represents the climax of the first half of “Dragon Lady.” Maria Sr., in many ways still a child herself, sings to her daughter, “I wish I could tell you that you are no child of pain / But you have my blood in your veins … / And trouble’s a family trait,” a haunting refrain that echoes turbulently throughout the generations.

The second half of “Dragon Lady” tells baby Maria’s side of the story. She’s 13 years old when we encounter her back in Washington, after Maria Sr. has moved to the U.S. with an American navy man who fell under her spell at the nightclub. He married her and gave her his last name, but this marital lifeline doesn’t have enough elasticity to withstand Maria Sr.’s past. As the eldest child, young Maria has no choice but to take over the childcare duties of her four younger siblings as her mother desperately tries to earn a living while simultaneously doing everything in her power to attract a new breadwinner for her family.

Porkalob is a vivid actor, but the dizzying array of squeaky children in the second half can make it hard to keep the story straight. Even so, the general picture of a mother’s absence and a daughter’s understandable resentment at having had to pick up the maternal slack in penurious conditions comes through loud and clear. At times there isn’t a single jar of baby food in the house, forcing Maria’s siblings to go out and beg for food donations. This scene seems plucked out of Charles Dickens, but we’re in the Pacific Northwest with a Filipino family and far removed from Victorian consciousness.

Porkalob doesn’t take sides in the conflict between her grandmother and mother. She gives both women their due, providing sufficient context to prevent us from jumping to judgment too quickly. There’s a mischievous element to Porkalob’s storytelling morality that is a direct result of Maria Sr.’s presence. Firing up her jukebox karaoke machine, this newly turned 60-year-old raps by way of introduction, “But I ain’t never killed a man that didn’t deserve it.” Words that we will see come true — at least if we are to credit her account, something her first-born daughter is less apt to do.

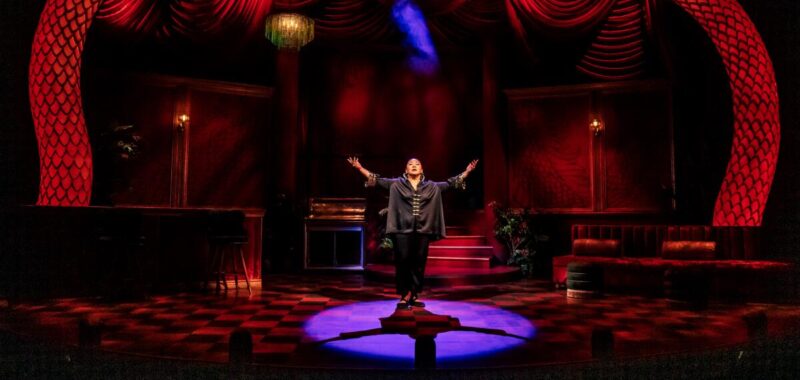

“Dragon Lady” works best as a one-person musical. Porkalob shares the stage with three extraordinary musicians (Pete Irving, Jimmy Austin and Mickey Stylin) who largely appear in the shadows of an inset space on the fabulous, garish red nightclub set by Randy Wong-Westbrooke. But she performs all the characters herself, and when she launches into song with her exquisite voice, moving from a range of high bell-like clarity to dusky lowdown in both original material by Irving and tweaked standards, the show is most fully alive.

When “Dragon Lady” becomes more of a conventional solo piece after intermission, a showcase for Porkalob to flex her versatility as an actor, the effect isn’t quite as powerful. One of the issues is that the tale being spun raises more plot questions than can be answered in the allotted time. Details and consequences are breezed over or ignored entirely, making “Dragon Lady” seem sketchy in places. When Porkalob is singing, however, the audience is too rapt to worry about a full narrative accounting.

Part 1 of the Dragon Cycle may not have found its ideal balance between music and drama, but Porkalob leaves a potent theatrical impression. Her family’s immigrant story must be exceedingly painful to relive, but it’s also clearly empowering. And not only for her but also for theatergoers who might feel that their own unsanitized histories couldn’t stand scrutiny on a public stage. “Dragon Lady” gives permission for the marginalized and the morally messy to belt out their complicated truths.