January 14, 2025

4 min read

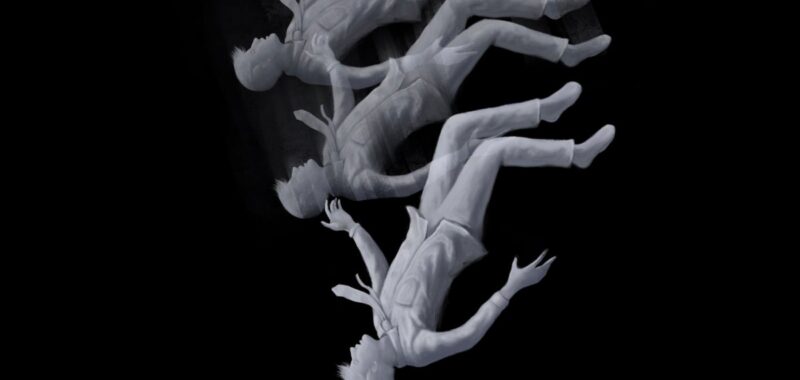

Why Are Recurring Dreams Usually Bad Ones?

Recurring dreams may feature taking a test the dreamer didn’t study for, having to make a speech or being attacked. Here’s why our sleeping brain comes back to these unpleasant dreams again and again

Jorm Sangsorn/Getty Images

Why does it seem like the same dreams keep following us? Maybe you’ve dreamed of soaring like a bird since childhood, or you’ve recently started revisiting a particular place or time while asleep. Perhaps a bad day at work still stirs exam nightmares, even if you haven’t been a student for decades.

If so, you’re far from alone. Recurring dreams are a surprisingly common phenomenon: research shows that up to 75 percent of adults experience at least one during their lifetime. These dreams exist on a spectrum: sometimes they’re nearly identical each time they occur, but they may also have recurring themes, locations or characters set against different backdrops. This fluctuation sets recurring dreams apart from bad dreams triggered by post-traumatic stress disorder, a psychological condition in which people relive specific memories from their waking life with far less variation while asleep. Experts are still uncertain about why we experience recurring dreams at all, but new research is helping better identify patterns in their frequency and content, as well as in the scenarios that provoke them.

Recent studies have bolstered the long-held idea that recurring dreams are often—but not always—bad ones. In a 2022 survey by Michael Schredl, head of the sleep laboratory at the Central Institute of Mental Health in Germany, and his colleagues, adults flagged recurring dreams as “negatively toned” two thirds of the time; these dreams often touched on themes such as being chased or attacked, arriving somewhere late or failing at something. The participants’ positive recurring dreams, by contrast, involved themes such as flying or discovering a new room in their house.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The reasons why we might have a greater propensity for negative dreams are not fully understood, but Schredl says dreams typically overdramatize something in our waking life—even a small feeling or minor situation we feel powerless to change. “In the dream, it becomes a much bigger emotion, although the connection isn’t always straightforward or obvious,” he explains.

Psychology and neuroscience offer additional clues. For example, we are prone to what’s known as negativity bias: a tendency to fixate more upon unpleasant thoughts, emotions or social interactions than on positive ones. This behavior is rooted in our subconscious need to resolve negative situations that threaten our survival. Negativity bias may be compounded in sleep because our dreaming brain dampens the areas associated with linear logic and activates portions associated with emotion, weakening the filter between our thoughts and our feelings.

Understanding the psychological underpinnings of recurrent dreams has been challenging to study because it’s difficult to control dreams in an experimental context. But events like the 9/11 terrorist attacks or the COVID pandemic, those in which many people experience a shared trauma, have allowed scientists to investigate certain dream-related patterns in more detail.

People who live through regional or global catastrophes often experience a “striking” increase in negatively-toned recurring dreams afterward, says Deirdre Leigh Barrett, a dream researcher and author of the 2020 book Pandemic Dreams. During the pandemic, Barrett amassed more than 15,000 dream reports, and in twin publications—a book chapter and a study—she showed that repeated themes involving fear, illness and death were then two to four times more common in peoples’ dreams than they were before the pandemic began. Common narratives included watching loved ones die, seeing swarms of insects (perhaps stemming from the description of COVID as a “bug,” Barrett says) and experiencing disasters, such as tidal waves, that are emblematic of something all-consuming.

Barrett found that dreams early in the pandemic tended to be more literal and induced more fear and anxiety. Over time, they shifted toward less terrifying but still unpleasant situations related to social embarrassment, such as being the only person in public not wearing a face mask. “They’re clearly somewhat linked to what’s going on in our daily lives,” Barrett says, referring to what is known as the “continuity hypothesis.” “If you’re not processing the emotions during the day, your nocturnal consciousness will attempt to process them at night,” she explains.

Barrett and other experts emphasize that negative recurring dreams are common and normal and that there are actionable steps to control them. Some people have found success in a practice called imagery rehearsal therapy, in which they repeatedly reimagine their nightmares with happier endings before going to sleep. Nirit Soffer-Dudek, a consciousness researcher and clinical psychologist at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Israel, also recommends cultivating good “sleep hygiene.” By setting a consistent sleep schedule, limiting screen use and avoiding caffeine or alcohol before bed, “you’re less likely to fall asleep while still in a heightened emotional state,” she says. “The best advice I can give is to try to enforce strong boundaries between your waking time and sleep to avoid bringing anxiety into your dreams.”